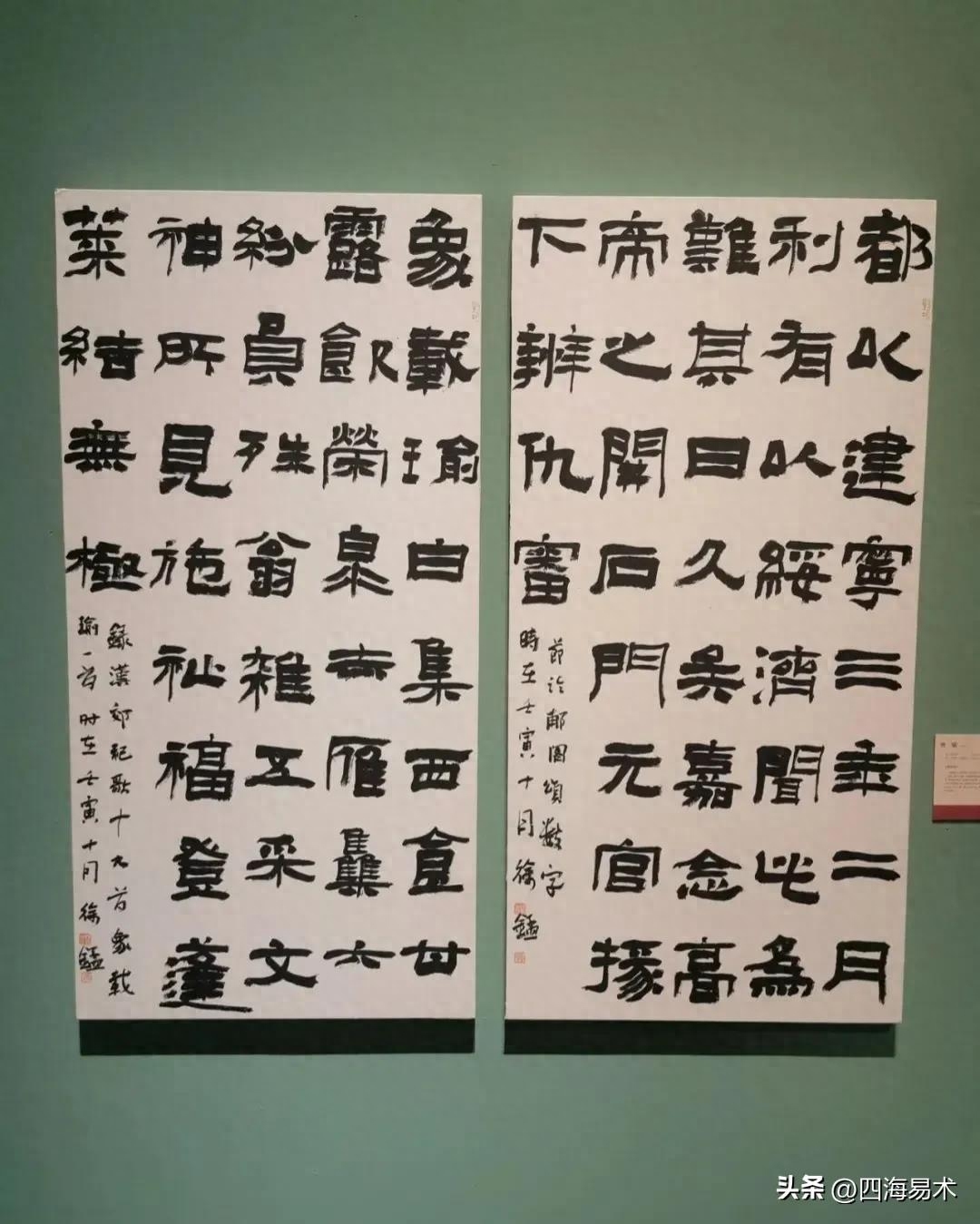

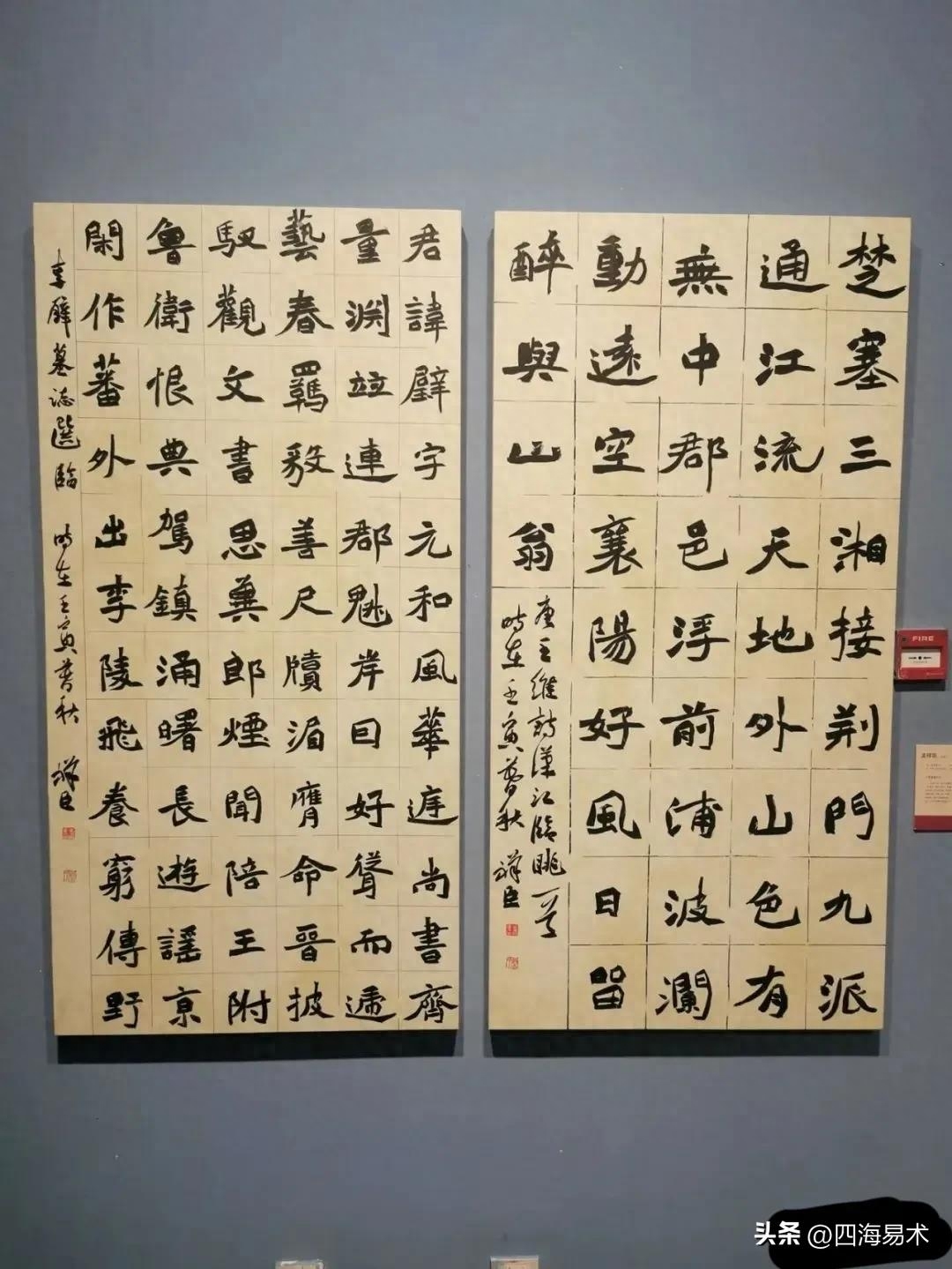

Typos will not be tolerated in calligraphy competitions. Here are ten commonly used traditional Chinese characters. Take a test and have fun. Each question is ten points. See how many points you can get.

Question 1: Can "Yang" be written as "Intestinal"?

"Yang" cannot be written as "". We know that "Yang, Yang, Yi, Tang" have all been simplified to "Yang, Yang, Chang, Tang", but only "Yang" has been simplified to "Yang". Why is this? This is because they are simplified in different ways. "Yang, Yang, Chang, Tang" are simplified by using the method of regularization in cursive script, while "Yang" is simplified by using the method of variant selection (some calligraphy incorporates this method into the homophone substitution method). "Yang" is selected from "Yang, Jie, Yang, Se, Fu, and Shu". Not only "yang", but also other things like "yin". "Yin" is chosen from "yin, yin, yin, guan, 阥, neon, and except". The "wu" on the right side of "Yang, Yang, Chang, Tang" is the cursive script of "昜". It can only be used as a simplified radical, not as the original character of "昜" (yáng). It is related to "昜" difference. When you encounter a word with the character "昜" next to it, you can generally shorten "昜" to "". However, when you encounter a character with the character "阳", you cannot shorten the "昜" to "", nor can you shorten it to "" "Yang" is abbreviated as "Yang" because "Yang" is a simplified character that cannot be used as a radical. For example, the cursive script of "Yi" is also "tang", but it is not regularized, so the "Yi" character of "Xi, Lizard, Ci" and other characters cannot be simplified.

Question 2: Why are the "Lu" characters next to "furnace" and "perch" simplified differently?

The "household" and "Lu" in "Lu, Lu, Lu, Donkey" and "舻, bastard, 賳, 渳, 垆" are all simplified by "Lu". They are both next to "Lu", why are they different? This is because the two sets of characters are simplified in different ways. The characters such as "Lu, Lu, Lu, Donkey" are selected from different scripts, while the characters such as "舻, bastard, 轳, 渳, 垆" are all written in cursive script. This means that the words "lu, lu, furnace, donkey" have ceased to appear a long time ago, and the "Kangxi Dictionary" has included these words. The characters "舻, bastard, 轳, 渳, 垆" and other characters are all derived from the radical "Lu" in cursive script. What I want to explain here is that when encountering rare ancient characters, if there is the word "Lu" in the structure, you can only write "Lu" and not "Hu".

Question 3:

What is the difference between "万" and "万"?

"万" and "万" were two words with different meanings in ancient times. Although "Wan" has not been seen in oracle bone inscriptions, it has already appeared in ancient records. It means "ten thousand". The original meaning of "Wan" is an insect. This insect is a kind of wasp, named "Wangai", with a pair of branched antennae on its head. "Wan" is a hieroglyph in both oracle bone inscriptions and bronze inscriptions, with a pair of tentacles on it, not the prefix "grass". Therefore, the "Zhuan Jing" says: "There is no grass in the yellow dream, and the stomach is afraid of thinking but not the field." Because "Wan Gai" "This kind of bee loves to live in groups, and there are many of them, thousands of them, so people gave it the meaning of the number "ten thousand", and later the two words became common. However, in compound surnames, "wan" is also pronounced as "m", such as "万俟". At this time, "wan" and "wan" cannot be used interchangeably. We cannot write "万俟" as "万俟".

Question 4: Is "fa" a direct simplification of "fa"?

"Fa" is not a direct simplification of "Fa". "Fa" is the simplified character of "Fa", which is simplified using cursive script. There is a sentence in "Wang Xizhi's Cursive Script Jue Song" that "you should record your decisions yourself, and you should pay attention to them when you send them." The "Fa" shaped like "Friend" here is the cursive version of "Fa". When the Chinese characters were simplified, the proximal sound was used to replace "Fa" with "Fa". Because "fa" is pronounced "fā", and "fa" is pronounced "fà", although the pronunciation of the two characters is close, they are not exactly the same, so it is called "near sound substitution". The simplification of "Fa" to "Fa" is an indirect simplification, that is, "Fa" is first simplified to "Fa", and then "Fa" (Fa) replaces "Fa". Some people are confused about the connection between them and think that "fa" and "fa" are the same word, so they write "barber salon" and "hair salon" as "barber salon" and "hair salon".

Question 5: Is "Ji" the traditional Chinese character for "GU"?

"Ji" is not the traditional form of "Guchi"

White text. In some cities, you can often see some shiny golden plaques: "Furniture City", "Furniture Store". It is said that many of these plaques were inscribed by some famous local calligraphers. Obviously, these "calligraphers" regarded "ju" as the traditional Chinese character for "gui". In fact, "gui" has not been simplified, so there is no such thing as traditional or simplified Chinese. Or someone might say: "Ju' and "Ju" can be used interchangeably." This is even more wrong! We should know that the word Tongjia can only be used in one way, and the two characters are not interchangeable. Indeed, in ancient Chinese literature, "Ju" is used to refer to "Ju", but this does not mean that "Ju" can be used to refer to "Ju". For example, in Sima Qian's "Historical Records: The Benji of Xiang Yu" there is a sentence: "You must come to thank King Xiang every day." The word "fleas" in this sentence can mean "zao", but we cannot use "zao" to mean "zao" in reverse, and write "fleas" as "jiao zao". Another example is the sentence "I will return home" in Tao Yuanming's "Peach Blossom Spring". The word "want" in this sentence corresponds to "invite", but we cannot conversely use "invite" to "want", and write "need" as "need to invite". There are many characters similar to this example in ancient Chinese, such as "Sun" can be connected with "Xun", "Shuo" can be connected with "Yue", etc.

Question 6: Is " fence " separated from " fence "?

" fence " is not separated from " fence ". "Li" and "Li" have been two words with different meanings since ancient times. Although the meanings of these two words have some overlap in ancient times, they are absolutely not the same. "Li" means "fence" or "fence". In ancient times, "笊力" was also written as "笊力". The meaning of "Li" is "tie fence". Therefore, when written in traditional Chinese characters, "笊笊" can also be written as "笊笊", but "笊甲" cannot be written as "笊盈". When the Chinese characters were simplified, the " fence " of "笊力" was replaced with the " 力" of " fence ". The simplified character "Li" contains two meanings: "笊利" and " fence"

Question 7: Can "eat" be written as "EAT"

"EAT" cannot be written as "EAT" under any circumstances. Some people think that "EAT" is a variant of "EAT". This is a misunderstanding. "Eat" and "eat" not only had different meanings in ancient times, but also had slightly different pronunciations. The ancient pronunciation of "Chi" is "qī", and its original meaning is "stuttering", that is, "stuttering". "Historical Records·Biography of Han Fei": "If you don't stutter, you can't speak, but you are good at writing books." The "stuttering" here means "stammering". The ancient pronunciation of "Chi" is "jī", and its original meaning is "eating", which means "eating". There is a line in Du Fu's quatrain poem "The plum blossoms are ripe and they can be eaten together with Zhu Lao". In some modern literary works, "eating" and "eating" are often used interchangeably. When the Chinese characters were simplified, "eat" was abolished and replaced with "eat". But when we write traditional Chinese characters, we cannot write "stuttering" (stuttering) as "stuttering"

Question 8: Is "駮" a variant of "PI"?

"駮" is not a variant of "PI". Some people think that "駮" and "PI" are the same character, which is wrong. The original meaning of "patch" is the impure color of the horse's coat, so the word "mottled" is still used in dictionaries today. Because the colors are different, the meaning of rejection is also derived, such as "refute", "criticize", "refute", etc. The original meaning of "駮" is a beast that looks like a horse. "The Classic of Mountains and Seas": "There is a beast in Zhongqu Mountain that is like a horse and has a black body, two tails and one horn, tiger teeth and claws, and a sound like a drum. It is called Zhan." In ancient times, there were people who mixed the two characters. Xu Shen of the Han Dynasty wrote in "Shuowen Jiezi" The meanings of the two words are separated. "Modern Chinese Dictionary" explains in the annotation that the two words are connected in the meanings of "refute, mottle", etc., but not in the meanings of "barge, barge", that is, "barge" and "barge", and cannot be written as "駮"Yun", "駮车".

Question 9: Can "ribbon-cutting" be written as "ribbon-cutting"?

If written in traditional Chinese, "ribbon-cutting" can be written as "ribbon-cutting". The original meaning of "cai" is "color", and the original meaning of "cai" is colored silk. When simplifying Chinese characters, the homophone substitution method is used, and "cai" is replaced by "cai". "Cutting the ribbon" means cutting the colored silk. What is being cut here is colored silk, not color, so when writing in traditional Chinese, you can only write "ribbon-cutting" but not "ribbon-cutting". Another example is "Lamps and festoons". In traditional Chinese, you can only write "Lengths and festoons" but not "Lengths and festoons". In the same way, the lanterns are hung here, and the ties are colored silk, not colorful. At the same time, "colored silk" cannot be written as "colored silk", because "cai" itself is colored silk. If it were written as "colored silk", it would be confusing.

Question 10: Can "curtain" and "curtain" be used interchangeably?

"curtain" and "curtain" cannot be used interchangeably. What is said here cannot be universal, and it is from the perspective of traditional Chinese characters. From the perspective of simplified Chinese characters, "curtain" can be connected to "curtain". Although "curtain" and "curtain" were used interchangeably in some ancient words (for example, "curtain" was also written as "curtain"), their original meanings are different. The original meaning of "curtain" is "curtain", which is a shielding device between doors or windows. In ancient times, what the emperor and princes set up was called "screen", what the officials set up was called "curtain", and what was set up by scholars was called "curtain". Later, these names gradually became confused, so there were words such as "curtain screen", "curtain curtain" and "curtain curtain". The original meaning of "curtain" is the "look" (ie "cover") made of cloth, and it also specifically refers to the wine flag, which is the cover in front of the hotel. Tang poetry: "Thousands of miles away, the oriole crows, the green reflects the red, and the wine flag winds in the mountains and rivers of water." The "wine flag" here is the "wine curtain". When the Chinese characters were simplified, "curtain" was used instead of "curtain". If written in traditional Chinese characters, "Jiu Lian" cannot be written as "Jiu Lian".

Dear book friends, can I get 90 points?

I am Sihai Yishu, and I share a little knowledge of calligraphy every day!

Articles are uploaded by users and are for non-commercial browsing only. Posted by: Lomu, please indicate the source: https://www.daogebangong.com/en/articles/detail/shu-fa-chuang-zuo-zhong-chang-yong-de-shi-ge-fan-ti-zi-mei-ge-zi-shi-fen-kan-kan-nin-neng-de-duo-shao-fen.html

支付宝扫一扫

支付宝扫一扫

评论列表(196条)

测试