Regarding this issue, South Korea said it could not afford to be hurt.

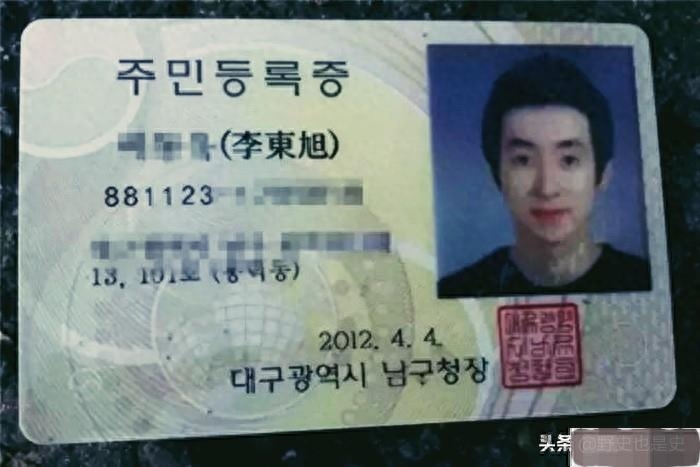

Since the implementation of the de-Chinese character movement in South Korea, Koreans have never stopped experiencing embarrassing consequences in terms of writing. One of the many embarrassments is the Chinese character names on ID cards.

What's even more serious is that Korean teenagers are unable to read their country's historical documents, because these documents were all recorded in Chinese characters.

What is also ironic is that the inscriptions in some historical attractions in South Korea are also recorded in Chinese characters. This situation has led to many Chinese tourists explaining the main meaning of the inscriptions to Koreans.

Chinese characters have been used in the Korean Peninsula for more than 2,000 years, and were introduced to the four counties of Han Dynasty during the reign of Emperor Wu of the Han Dynasty. Since then, Chinese characters have become the only official written language on the Korean Peninsula.

In order to solve the reading problem of the peninsula people, a method of borrowing the sounds or meanings of Chinese characters and expressing them according to Korean grammar was invented. This method was later called "official reading".

However, with the expansion of people's cultural knowledge, the "official reading" method cannot meet the needs.

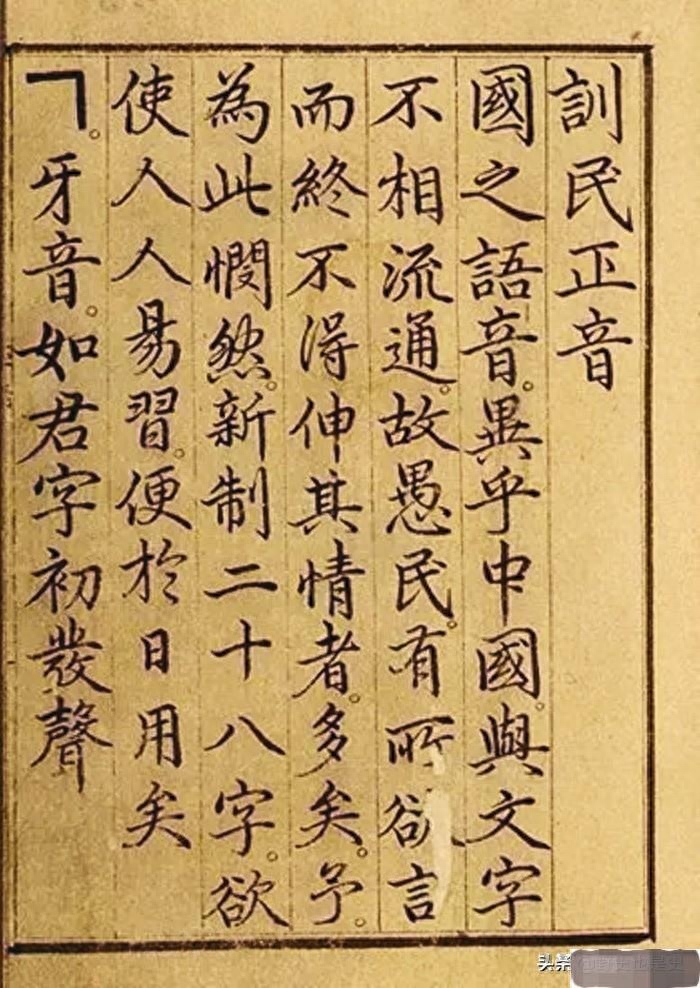

In 1446, King Sejong of Joseon promulgated "Hunminjeongeum", which is a phonetic script composed of 28 letters, which is what we now call "Hyeonmun".

It is well known that learning Chinese is difficult, and proverbs are designed to meet the daily needs of ordinary people. Syllables are formed by combining proverb letters and are used to spell Chinese characters.

The 24 Hangul letters used in modern Korea evolved from the original 28 Hangul letters.

At that time, proverbs were only an auxiliary tool, and the scholar-bureaucrats still used Chinese characters as writing tools. They believed that proverbs were just a "dialect" and could not be refined.

This belief lasted until the end of the 19th century. After the Sino-Japanese War, the status of Chinese characters began to decline on the peninsula, and the style of pure Chinese characters began to transform into a mixed style of Korean and Chinese.

After Japan occupied the peninsula, schools began to completely cancel Korean courses. After Korea was restored to independence, some cultural scholars began to call for the use of Korean throughout the country, and the de-Chinese character movement began to rise.

In 1948, South Korea stipulated that official documents could only use Korean, and only additional clauses allowed the use of Chinese characters and phonetic characters. Twenty years later, South Korea banned the use of Chinese characters and forcibly abolished them from textbooks.

In 1970, Chinese characters were abolished in all primary and secondary school textbooks in South Korea, and phonetic characters were used entirely.

At this time, South Korea was bent on emphasizing the national cultural crisis, but ignored that Chinese characters had been spread on the peninsula for more than 2,000 years. Complete cancellation would cause a historical and cultural disconnect.

The official documents, historical works and literary works of the peninsula in ancient times were all written in Chinese characters. De-Chinese characters will bring a vacuum of history and culture, and many names of people and places will be ambiguous.

For Koreans, de-Chinese characterization is a manifestation of national pride, but they are unaware of the consequences of this overcorrection.

It is obviously impossible to completely get rid of the shackles of the Chinese character culture circle for more than two thousand years through a one-size-fits-all approach.

70% of the more than 500,000 words in Korean are Chinese characters. If Chinese characters are abandoned, it will be difficult for the people to fully master the language of their own nation, and reading historical documents will be like reading a book from heaven.

40% of South Korea’s products are exported to the cultural circle with Chinese characters, and 70% of tourists come from the cultural circle with Chinese characters. Many young Koreans cannot see the Chinese names marked on each other’s business cards.

In the face of a new "cultural crisis", some people of insight began to call for an end to the de-Chinese character movement.

South Korea has begun to revise its policy on eliminating Chinese characters, stipulating that middle schools can use 1,800 Chinese characters and restoring Chinese to junior high schools.

In 1999, South Korea issued a new plan requiring the use of both Korean and Chinese characters on government documents and traffic signs.

Korean is a phonetic script, and it is difficult to distinguish words with the same pronunciation but different meanings. For example, "character" and "mosquito" have the same pinyin, but their meanings are different. Koreans can only guess the meaning based on the context.

The pronunciation of one Korean word may mean the meaning of several words. If you only read Korean, it is difficult to understand its meaning. Especially with names, sometimes if you call one person, several people may agree.

In order to avoid this ambiguity, the Korean name on the Korean ID card has a Chinese character name under it to distinguish it. This is also the case with the Chinese characters on Korean road signs.

It is very difficult to understand pure Korean, and it must be inferred based on the context. Just like when we are reading a pinyin article, the reading difficulty will increase a lot.

In order to solve this dilemma, South Korea announced in 2005 that all official documents and traffic signs would fully resume the use of Chinese characters and Chinese character marks.

There are still many difficulties caused by the de-Chinese characterization, the most important one is the historical and cultural gap. If Chinese characters are completely removed, ancient Korea will be completely cut off. The consequences are unimaginable.

To sum up, the use of Chinese character names on Korean ID cards is mainly to avoid ambiguity and misunderstanding. It can also be regarded as a way to "make up for the situation" in the de-Chinese characterization movement.

This is interesting to say. It is said that after the founding of South Korea in 1948, Chinese characters were abolished. There are two main reasons: First, to prove that they are a "completely independent" country; second, they believe that learning Chinese characters is too difficult and not as easy as learning Korean characters.

Korean characters are phonetic characters, and Chinese characters are ideographic characters. What's the difference between the two? Well, let me use an analogy. If one day, we no longer use Chinese characters to write, but instead use Chinese Pinyin, and there is no intonation marking, how would you feel reading such a large number of Chinese Pinyin texts? After South Korea abolished Chinese characters, it is just like the Chinese pinyin without tones. If you don’t read the articles and sentences from beginning to end, you may not be able to understand the meaning. What's even more terrible is that because it has no tone, it is easy to "express the wrong meaning." Take the Chinese Pinyin as an example. For example, fangshui, you can understand it as meaning waterproof, water release, someone to protect against, someone to release, and room tax. If you don't read it from beginning to end, you won't be able to correctly understand what it means when you see this fangshui. Because of this, Koreans have been marking their ID cards with Chinese characters in recent years to prevent confusion.

In addition, due to South Korea's active promotion of education to remove Chinese characters, fewer and fewer people in South Korea understand Chinese characters. This resulted in a ridiculous consequence. Since Korean historical classics and documents are all written in Chinese characters, today after the abolition of Chinese characters, many Koreans have no idea what their ancestors were writing if they don't read the translation. On the contrary, Chinese people who travel to South Korea do not need to find someone to translate Korean historical classics and documents when looking at them. As long as you know how to read classical Chinese, you can understand what is written. Think about this country, nicknamed by netizens as "the most powerful country in the universe". It competes with us every day for the four great inventions, Li Bai, Du Fu, Qu Yuan, Dragon Boat Festival, Mid-Autumn Festival... but it can't even understand what its ancestors wrote. It's really It's pitiful, infuriating and ridiculous. This is why more and more people in South Korea are calling for the restoration of Chinese characters.

Articles are uploaded by users and are for non-commercial browsing only. Posted by: Lomu, please indicate the source: https://www.daogebangong.com/en/articles/detail/han-guo-jin-dai-fa-dong-qu-han-zi-hua-yun-dong-wei-shen-me-ru-jin-shen-fen-zheng-you-kai-shi-shi-yong-han-zi-le.html

支付宝扫一扫

支付宝扫一扫

评论列表(196条)

测试