One year, the History Institute of the Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences held a seminar on the "August 13th Songhu Anti-Japanese War". The topic was a batch of "August 13th" photos that Mr. Xiong Yuezhi got when he visited Germany. After finishing the main topic, he also mentioned the so-called "falsification" of the photos of the atrocities committed by the Japanese army① by Nobukatsu Fujioka of the University of Tokyo, saying that it should be taken seriously. Before I finished speaking, a retired gentleman immediately questioned, thinking that "we Chinese have the final say on these matters, and we don't have to pay attention to what the Japanese say." Similar opinions have been heard on other occasions, and it is not "accidental", so I also responded on the spot. The general idea is: although you don’t need to pay attention to the self-promotion of Japanese right-wing scholars, you can’t let the problem itself go away; every “false” photo proposed by Japanese right-wing scholars has a history, content, and even “interpretation” The need for a thorough review is not only because of the "problem" context of the right-wing challenge, but also because many photos are inherited from the predecessors, and the future use is basically "Chen Chen Xiangyin" (I use this term without praise or criticism) , today, after a lapse of several decades, it is indeed necessary to "return the original to the end" and make a thorough cleanup. Although we were only talking about photos at the time, in fact, I think the same should be true for other materials such as texts and real objects, and related research on Japan, especially research with different opinions. The biggest difference between the Nanjing Massacre and general historical events lies in its "righteous name" in the old saying, but as a "historical event", I think it should not be totemized; since I am confident that it is a "truth", from " In terms of "utility", there is no need to worry about academic examinations, and there is no need for immunity from examinations. At the end of last year, the 28-volume "Nanjing Massacre Historical Materials Collection" was published. Nanjing University, Nanjing Normal University and other units jointly held the "International Academic Symposium on Nanjing Massacre Historical Materials". , making people feel that “discussion has become possible” on this famous historical event that affects sensitive nerves outside the academic world. I have always had a prejudice, thinking that if we adhered to academic standards and were more "flexible", many views of Japanese right-wing scholars would have been self-defeating, at least they would not have as much market as they do now③. This is a prominent experience that I have paid attention to related research in Japan for many years, and it is also an important reason for me to continue to pay attention to related research in Japan④.

The "historical materials of the Nanjing Massacre" mentioned in this article take the usual broad meaning. Regarding this point, a little explanation must be made first. 1. Although "Nanjing Massacre" (Nanjing Massacre) was once used by the mainstream of the Japanese massacre faction as the correct name for the historical events that occurred when Nanjing fell in late 1937, such as the writings of Mr. Tomio and others⑤, it is not a general term in Japan. During the Tokyo Trial, this historical event was called the "Nanking Atrocity Incident" (the Japanese and Chinese characters are the same, or the English translation of Nanking Atrocities is "Nanjing アトロツティズ"). Today, apart from Michio Tsuda, Kenji Ono and other individual scholars still insist on Using "Nanjing Massacre"⑥, the mainstream of the massacre school is gradually using the name "Nanjing Incident"⑦; when the Japanese fictional school calls "Nanjing Massacre", they must add quotation marks to indicate that it is a "so-called" massacre. Some people added quotation marks to "event", which means that nothing happened at that time, and "event" was also "fabricated"⑧. But generally speaking, the "Nanjing Incident" is a "convention" in Japan. The "Nanjing Massacre materials" referred to in this article are the "Nanjing Incident materials" in Japan. This does not contradict what is usually meant. 2. Although domestic academic circles have clear and strict definitions of the connotation of the Nanjing Massacre, especially key points such as the number of people, they are very "lenient" in the selection of materials. The exact meaning of some literature, such as what can be proved? To what extent can it be proved? What is the meaning of the whole text? Does the excerpted paragraph match the spirit of the whole article? Is the material itself reliable? Especially the authenticity of some oral records, such as whether there is "freedom of expression" in the interview environment? Does the interviewer have "leads" or hints to the interviewee? Is what the interviewee said realistic? If measured by the scale of history, it cannot be said that all of them have been strictly checked and answered satisfactorily. This is an important reason for the same material to draw different or even opposite conclusions. Therefore, this article does not "judging people by their appearance", and the main materials of the "Nanjing Incident" compiled by various factions are within the scope of the discussion.

This article is divided into two parts, the first part briefly introduces the relevant Japanese historical materials, and the second part summarizes the value of Japanese historical materials. The next part is the focus of this article.

Part 1

The three factions in Japan (the massacre faction, the centrist faction, and the fictional faction) who hold different positions on the "Nanjing Incident" all compiled data sets as evidence for their own views. According to the form, there are two categories: literature and oral, and according to the source, there are Japanese translations of Japanese official and private documents and Western and Chinese documents. The following is an introduction to the collection of materials in the order compiled by the massacre, the middle, and the fictional factions.

1. Slaughter faction

1. "Nanjing Incident"

Edited by Dong Tomio, published by Haide Shobo in 1973. This book is a kind of "Materials on the History of the Japan-China War", which is divided into two volumes I and II (Volumes 8 and 9 of "Materials on the History of the Japan-China War")⑨. Volume I contains the Japanese records of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East related to the "Nanjing Incident", which are divided into five parts, namely: (1) Indictment, (2) Trial shorthand, (3) Unread court evidence (documentary evidence of the prosecution) , (4) Not to submit documentary evidence (including the prosecution and defense), (5) Judgment.

The trial shorthand in Volume I is the largest, including the answers from the former doctor of Jinling University Hospital (referring to the doctor at the time of the incident, the same below) Robert O. Wilson in court to the prosecution and defense on July 25, 1946 As of April 9, 1948, General Matsui Iwane, Commander of the Central China Front ⑩, had 26 twists and turns in the courtroom in the final debate between the prosecution and the prosecution. The main contents are: (1) Wilson, Xu Chuanyin, vice president of the Red Swastika Society, Nanjing citizen (Nanjing citizens are not specified otherwise) Chen Fubao, professor Miner Searle Bates of Jinling University, and Lieutenant Liang Tingfang of the Chinese Army Medical Department (sic) , Matsui Iwane, Minister-at-large Ito Shushi, Deputy Chief of Staff of the Central China Front Army Akira Muto, Anglican Church Priest John Gillespie Magee, Chief of Staff of the Central China Front Army Ningito Nakayama, Counselor of the Japanese Embassy in Nanjing Rokuro Hidaka , Senior Official Koji Tsukamoto, Minister of Justice of the Shanghai Dispatched Army, Director of the East Asia Bureau of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan Ishisa Inotaro, Chief of Staff Mitsuo Nakazawa, Chief of Staff of the 16th Division, Major General Mamoru Iinuma, Chief of Staff of the Shanghai Dispatched Army, and Oka, a special entourage of the Shanghai Dispatched Army Witness Tian Shang appeared in court successively to answer cross-examinations by the prosecution, the defense, or both parties. (2) The prosecutor read successively Shang Deyi, Wu Changde, Chen Fubao, Liang Tingfang, Professor Lewis S.C.Smythe of Jinling University, Director of the YMCA George A.Fitch, Chen Ruifang, pastor of the American Christian Missionary Mission James H.McCallum, Sun Yongcheng, Li Disheng, Written testimony of Luo Songshi, Wu Jingcai, Zhu Diweng Zhang Jixiang (same document), Wang Kangshi, Hu Duxin, Wang Chenshi, Wu Zhuqing, Yin Wangze (11), Wang Panshi, Wu Zhangshi, and Chen Jiashi And Matsui Iwane's statement on December 19, 1937, the report on the cruel behavior of the Japanese army submitted to Zhe Jun and others on behalf of the prosecution (12), the "Nanjing Safety Zone Document" compiled by Xu Xishu (13), and Lusu's report in the report of the prosecutor of the Nanjing District Court Testimonies, Nanjing District Court Prosecutor's Office "Investigation Report on Enemy Crimes", the report of the US Embassy in Nanjing on the situation in Nanjing from December 1937 to the following year, the interrogation records of Akira Muto, the summary of the proceedings of the Budget Committee of the 73rd Session of the Aristocratic Council (Dazang Gongwang asked, Kido Koichi answered). (3) The court successively reviewed Matsui Iwane's statement on December 18, 1937, the "Notice to Persuade Surrender" on December 9 of the same year, and the speech of the Minister of Intelligence of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan published in "ジャパン·アドバ-タィサ-" on December 1 of the same year, On November 16 of the same year, the "Tokyo Nihonshimbun" discussed whether Matsui Iwane's report on "aid" to Jaquinot and others in setting up the Nanshi Refugee Area was admissible as evidence for the defendant (the results were all rejected by the court). (4) The defense lawyers successively read out Hidaka Shinrokuro, Tsukamoto Koji, Nakayama Ningren, Ishisa Inotaro, Minister of Education and Culture Koichi Kido, Second Lieutenant Osugi Hiroshi, the Observation Squad of the First Brigade of the Third Regiment of the Field Artillery of the Third Division, and the Second Lieutenant Hiroshi Osugi of the Third Division Second Lieutenant Ouchi Yoshihide, Acting Squadron Leader of the Seventh Squadron of the Ninth Regiment of the Tuanshan Artillery Corps of the Ninth Division, Colonel Wakisaka Jiro, Commander of the 36th Regiment of the Ninth Division, and Nishi Nishi, Captain of the First Battalion of the 19th Infantry Regiment Written testimonies of Major Shimao Takeshi, Mitsuo Nakazawa, Mamoru Iinuma, Minister of Justice of the Tenth Army Sekiro Ogawa and senior officials, Chief of Staff of the Shanghai Expeditionary Army Major Sakakibara, Director of the Greater Asia Association Saburo Shimoya, and members of the Nanjing Safety Zone International Committee Letter from Minister John H.D. Rabe (abstract), written testimony of James H. McCallum (abstract), report by James Espy, vice-consul of the U.S. Embassy in Nanjing, telegram from Joseph Clark Grew, U.S. ambassador to Japan, to the U.S. State Department at noon on February 4, 1938, Matsui Iwane's "Instruction" on December 18, 1937, "Jinshan Temple Announcement" by the Shanghai Dispatch Army, photos of the altar of the Guanyin Hall built by Matsui Iwane, Matsui Iwane's statement on December 18, 1937, and "Letter to the People of the Republic of China". (5) Prosecution and defense statements and arguments.

Unread court evidence includes: (1) Enemy massacres reported by Nanjing Charity Group and Lusu. (2) Statistical table of the number of corpses buried by the Chongshantang burial team. (3) Statistical table of the number of corpses buried by the burial team of the Nanjing Branch of the World Red Swastika Society.

Documentary evidence not submitted includes: Prosecutor: (1) "Tokyo Daily Shimbun" reported on the competition of hundreds of people beheaded. (2) Katsuo Okada sworn statement. (3) Written testimony of Huang Junxiang's witness. (4) Statement by Frank Tilman Durdin. (5) "The massacre of local people in China by the Japanese army in Nanjing, the disarmed soldiers and the burial of corpses by the Nanjing Red Swastika Society". (6) "Photography of the Burial Places of the Victims of the Nanjing Massacre in the 26th Year of the Republic of China". (7) Crimes against humanity - China Confirmation Letter (original letter from the Chinese government). Defense: (1) Summary of "Osaka Asahi Shimbun" on December 10, 1937 ("Wounded Soldiers Rejected, Extremely Inhuman Chinese Army"). (2) Summary of "Osaka Asahi Shimbun" on December 10, 1937 ("The Chinese Army's Crazy Destruction Surprised Foreign Military Experts"). (3) Summary of the North Branch Edition of "Osaka Asahi Shimbun" on April 16, 1938 ("The Work of Disposing of Corpses—Facing the Rampant Period of the Epidemic, the Epidemic Prevention Committee's Great Activities").

The judgment includes: (1) Chapter II = Law (read out on November 4, 1948) (ハ) the indictment part. (2) Chapter VIII = "Nanjing Atrocities Incident" of "Normal War Crimes". (3) Chapter 10 = "Determination" of Matsui Iwane. (4) Judgment of Judge Radhabinod Pal on behalf of India, Part 6 = "War Crimes in the Strict Sense" Part 2 "War Crimes in the 'Strict Sense', Causes of Action for Ordinary People in the Areas Under Japanese Occupation" Fourteen and fifty-five".

In addition to problem solving and explanations, Volume II includes 4 kinds of documents, including: (1) What is War——Atrocities of the Japanese Army in China, edited by H.J. Timperley (14); "; (3) Lewis S.C.Smythe, "The Disasters of War in Nanjing——A Survey of Urban and Rural Areas from December 1937 to March 1938"; (4) F. T. Durdin, Nanjing correspondent of The New York Times.

The collection in this book is the basis for determining the date of the “Nanjing Incident” for the first time. Although, just like the Tokyo Trial itself was questioned and dissatisfied from the very beginning (15), there is always ambiguity about these basis, but because the Tokyo Trial With an authoritative title of "international", no matter what position you take to defend, revise, or oppose, you cannot bypass the evidence and conclusions of the Tokyo Trial. If one traces back the debates in Japan about the Nanjing Massacre, almost all the main issues can be found in the Tokyo Trial. Therefore, even today, with the excavation of various documents, especially as the debate has shifted from the court to the "academic circle" (16), there is more or less room for leisurely discussion, and the understanding of the Nanjing Massacre has deepened. Income still has irreplaceable value.

2. "Nanjing Incident Data Collection"

Compiled by the Japan "Nanjing Incident Investigation and Research Association" (17), published by Aoki Shoten in October 1992. This collection is divided into two volumes, the first volume is "U.S. Relations Materials", and the second volume is "China Relations Materials".

The first volume includes: commentary, Part I "Nanjing Incident recorded in documents", Part II "Nanjing Incident reported by news", appendix "Interview materials of F. T. Durdin and Archibald T. Steele". Among them, Part I includes: (1) Nanjing air raid; (2) Panay and Ladybird incidents; (3) the situation in Nanjing; (4) Nanjing International Refugee Area; (5) brutal behavior of the Japanese army. The second volume includes: Explanation, Part I "Nanjing Incident in News Reports", Part II "Nanjing Incident as Seen in Books and Materials", Part III "Records of Burial of Remains", Part IV "Materials of Nanjing Military Trial", Appendices 1 "Catalogue of Chinese Records Related to the Nanjing Incident", 2 "Catalogue of Main Chinese Data Collections".

The second volume is mainly based on the "Historical Materials of the Nanjing Massacre by the Japanese Invaders" compiled by the Nanjing Library, the "Archives of the Nanjing Massacre by the Japanese Invaders" compiled by the Second Archives and the Nanjing Municipal Archives, and the "Nanjing Defense War—— Former Kuomintang Generals' Personal Experience of the War of Resistance Against Japan", Kuomintang Party History Society compiled "Revolutionary Documents" and "Ta Kung Pao" and other newspapers.

Most of the collections in the first volume of this book are collected for the first time (18), and many materials are quite difficult to find. Moreover, as a "third party" other than China and Japan, at least they will not be favored because of "national sentiments". This is the special significance of this edition.

3. "Nanjing Incident Kyoto Division Relations Data Collection"

Edited by Kazuki Iguchi, Junichiro Kisaka, and Masaki Shimosato, published by Aoki Shoten in December 1989. This is a collection of the diaries of Masuda Rokusuke, Ueba Takeichiro, Kitayama Yo, Makihara Nobuo, Higashishiro, Soda Six Assistants' diaries, Kamiba Takeichiro's notes and Diary of the 4th Squadron of the 20th Wing, and the rear of the 12th Squadron. There are also two problem-solving articles: Iguchi Kazuki "Kyoto War Exhibition Movement and Data Excavation" and Shimosato Masaki "Nanjing Raiders and Lower-level Soldiers".

The 16th Division was one of the main force of the Japanese army to capture Nanjing. This edition is the first time that the original records of the Japanese soldiers during the war are published in a concentrated manner (19). As one of the editors, Shimosato Masaki said, the perpetrator "does not confess to himself", from which we can actually and concretely feel the "direct and indirect causes" of the Nanjing Massacre (20).

4. "Soldiers of the Imperial Army Recording the Nanjing Massacre"

Compiled by Kenji Ono, Akira Fujiwara, and Katsumoto Moto, published by Otsuki Shoten in March 1996. This collection includes 16 members of the Yamada Detachment of the 13th Division of the Sendai Army (21) "Saito Jiro" of the 65th Regiment of the Aizu Wakamatsu Infantry (22) and "Kondo Eishiro" of the 19th Regiment of the Echigo Takadayama Artillery Regiment 19 diaries of 3 junior officers and soldiers.

The main editor of this editor, Mr. Kenji Ono, is not in the academic world (he calls himself a "laborer"), and the interviews and collections are carried out in his spare time all year round, which is not easy (23), which is touching. The greatest significance of this edition is to prove that most of the 14,000 Chinese officers and soldiers captured by the "Two Corners" (24) in Mufu Mountain were shot to death during the war (25).

5. "Battle of Nanjing·Searching for the Sealed Memory—Testimonies of 102 Former Soldiers"

Edited by Matsuoka Ring, published by Social Review Agency in August 2002. The "testimonies" collected in this collection include the Japanese Kanazawa Ninth Division (6 people), the Nagoya Third Division (5 people), the Kumamoto Sixth Division (1 person), and the No. 2 Anchorage of the 38th Army (4 people), the soldiers of the 11th Squadron of the Third Fleet (1 person), mainly soldiers from the 16th Division (85 people), of which the 33rd Wing had the most (59 people).

Among all the interviews so far, this editor has the largest number of interviewees. The efforts made by Ms. Matsuoka and Mr. Lin Boyao, a Chinese businessman in Japan, in the "adversity" are worthy of appreciation, but there are also different evaluations among the Japanese massacre faction (26).

Second, the centrist

6. "Nanjing War History Collection"

Edited by the Nanjing War History Materials Compilation Committee, published by Peer Press in November 1989. It is the most important seven parts: Diary, Combat Order, Ultimatum, Instruction, Combat Process Summary, Wartime Report, Battle Detailed Report, Battle Log, Chinese Intelligence, Third Country Intelligence, War History Research Notes, and Wartime International Law It is the first three parts.

The diary section includes "General Matsui Iwane Battle Diary", "General Matsui

This edition is edited by the old Japanese military group, and the editorial board members are all old soldiers except Itakura Yuaki (author of "The Truth Is Such as the Nanjing Incident"). As shown in the title, strictly speaking, this edition is not a collection of "Nanjing Massacre" or "Nanjing Incident", but because Japan ordered the burning of wartime documents twice at the end of the war and before the Tokyo Trial, the relevant documents have been exhausted. There is no one, so even the scattered literature on "war history" is still valuable for understanding what the Japanese army did in a broader perspective. The feature of the diaries of Japanese officers and soldiers collected in this edition is that they include all levels below the highest officer, which is different from the data collection compiled by the massacre faction, which only includes soldiers and junior officers.

7. "Nanjing War History Collection" Ⅱ

Edited by the Nanjing War History Materials Compilation Committee, published by Peer Press in December 1993. The main content of this collection is a diary, and there are also some other documents. This edition is marked with "II", but it seems that it was not planned when the previous edition was edited, because the previous edition was not marked with "I", and the content was slightly repeated. Including: "General Matsui Iwane's Battle Diary" (full text), "General Matsui's Diary of the China Incident" (same as the previous edition), "Army General Hata Toshiro's Diary (Outline)" (same as before), "Sugiyama Letters" (same as above), "Conversation between Commander Matsui and Mihiko Yamamoto", "Memoirs and Responses of Major General Kawabe Torashiro", "Strategies for the Central Government of China", "Diary of Toshimichi Uemura" (previously edited from December 1 Beginning of the day, this edition starts from August 15th), "Diary of Yamada Kaiji", "Notes of Ryoko Industry", "Diary of Kiyomi Arami", "Diary of Takashi Odera", "Diary of Shigetoshi Sugawara", "Infantry No. Diary of the 12th Squadron of the 36th Regiment", "Diary of the 47th Infantry Regiment", "Operation Records of the 1st Squadron of Tanks", "Confessions of Toshio Ota", "Diary of Kenro Kajitani", "Rules for the Handling of Prisoners", "Official Lists of the China Incident", "Report of Lieutenant Commander Nishi Yizhang, Headquarters of the Army Department", "Foreign Newspapers", "Concept, Construction and Function of Defense Fortifications in Nanjing, Shanghai, and Hangzhou", "Nanjing The Construction of the Fortification of the City and the Battle of Defending the City", ""Joining the Army is Walking" - Notes of Sato Shinshou", ""Nanjing!! Nanjing!! News Anonymous Monthly Review".

Every time the Japanese right wing burns wartime documents with "regret", it seems that otherwise it can "clear up its innocence" for the Japanese army (28). In fact, the Japanese military and political authorities and those involved in the case at that time regarded these documents as hidden dangers and feared that they could not be completely removed. For example, Matsui Iwane's diary is still there, but he lied in the Tokyo court that it had been burned. The "full text" (29) of Matsui's diary collected in this edition was "discovered" by Hara Tsuyoshi (Small Slaughter faction), a researcher at the War History Department of the Japanese Defense Research Institute, after the publication of the previous edition. The diaries of senior Japanese generals collected in this and previous editions are very important for a comprehensive understanding of the background of the "Nanjing Incident" and the decisions made by the highest levels of the Japanese army, especially the Central China Front Army and the Shanghai Expeditionary Force.

Third, fictional school

8. "Jiwen·Nanjing Incident"

Aruo Jianyi, published by Book Press in August 1987. A total of 35 interviews and addenda were collected. The interview records are: "Testimony of Captain Onishi, Chief of Staff of the Shanghai Dispatched Army", "Testimony of Okada Naoshi, Attaché of Commander Matsui", "Testimony of Major Okada Yuji, Member of the Shanghai Dispatched Army's Special Affairs Department", "Tokyo Daily Testimony of photographer Yoshio Kanazawa", "Testimony of photographer Jiro Nimura of the Hochi Shimbun", "Testimony of Hirosaku Goto, reporter of Osaka Mainichi Shimbun", "Testimony of Yoshinaga Park, Chief of Staff of the Tenth Army", "No. The Testimony of the Tenth Army Staff Admiral Tanita Nagata", "The Testimony of the Tenth Army Staff Officer Kaneko Rensuke", "The Testimony of the Tokyo Daily News Reporter Jiro Suzuki", "The Testimony of the Tokyo Daily News Photographer Shinju Sato", " Testimony of reporter Masayoshi Arai of Dome News Agency", "Testimony of Tatsuzo Asai, Photographer of the Video Department of Dome News Agency", "Testimony of Kazuo Adachi, a reporter from Tokyo Asahi Shimbun", "Testimony of Tomi Saburo Hashimoto, Deputy Director of Shanghai Branch of Tokyo Asahi Shimbun" , "Testimony of reporter Toshisuke Taguchi from the Hochi Shimbun", "Testimony of reporter Akio Koike from the Metropolitan News Agency", "Testimony of Tetsuo Higuchi, a photographer from the Yomiuri Shimbun", "Testimony of Takashi Homo, a radio technician from Domendo News Agency", "Testimony of Captain Takashi Terasaki, Captain of Gunboat Seta", "Testimony of Reporter Mitomakanosuke from the Fukuoka Nikichi Shimbun", "Testimony of Ine Sumiya, a Marine Graphic Correspondent", "Shinji Doi, Captain of Gunboat Hira Testimony of Yoshio Watanabe, Special Photographer of the Intelligence Department of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Testimony of Haramoto Yamamoto, Member of the Shanghai Branch of the Osaka Asahi Shimbun, Testimony of Senbo Photographer of the Yomiuri Shimbun, and Shanghai Naval Attaché Testimony of Lieutenant Shigemura Minoru, who served as a government report", "Testimony of Shigeharu Matsumoto, Shanghai Branch Director of Tongmeng News Agency", "Testimony of Fukushima Minbo Shigoro Arrowai", "Testimony of Minoro Genda, Staff Officer of the Second United Air Force", "Planning Testimony of Mrs. Okada Yoshimasa, Secretary of State, "Testimony of Eiichi Iwai, Consul Officer", "Testimony of Tsujiichi Koyanagi, Member of the Army Reporting Team", "Testimony of Takao Mr. Susuya, Consul Officer", "Wild Run Testimony of Mikuni Naofuko, Commander of the Twenty-Second Regiment of the Army. The addendum explains the communication with 32 parties involved, including Chief of Staff Matsuda Chiaki of the Shanghai Expeditionary Army. Some of them refused to be interviewed by themselves, some refused because of their family members because of their age, some died during the contact, and a few gave a brief reply. Among those who refused to be interviewed, most of them believed that the Nanjing Massacre was an "unexpected event" and it was useless to talk about it; a few were unwilling to talk about it because they doubted the author's position. The popular "hundred people beheaded" (the perpetrator was sentenced to death by the Nanjing court after the war), while refusing it, he specifically said: "I hope you will not join the chorus of militarism that denies this 'century' massacre." ( 30)

9. "Testimony of 48 Japanese in the "Nanjing Incident""

Edited by A Luo Jian, published by Xiao Xiao Guan in January 2002. This edition is the "library version" of "Jiwen·Nanjing Incident" (31). The layout has been adjusted, with the exception of a small number of deletions in some interviews, the testimony of Matsumoto Shigeharu, director of the Shanghai branch of the Tongmengsha, has been deleted, and the new Aichi Shimbun reporter Minami Masayoshi, Chief of the General Affairs Section of the General Staff Headquarters, Isayama Haruki, and the Ministry of Army Arrow rewrote the epilogue of the testimony of Major Akira of the Military Division of the Military Affairs Bureau (32), the recommendation of Sakurai Yoshiko, and the publisher's "Written on the occasion of Bunko". Sakurai called this book the "first-level material" of the "Nanjing Incident"; the biggest difference between Arrow's new and old postscripts is that the new postscripts specifically emphasize that the Japanese army only "executed" soldiers in Nanjing, but did not commit crimes against civilians.

In terms of data sets, there are also ready-made materials completely translated from China or field investigations in China, such as "Testimony, Nanjing Massacre" translated by Mitsuyuki Kagami and Mitsuyoshi Himada (first edition of Aoki Bookstore in 1984), "Nanjing Incident Present Field Investigation Report" (Nanjing Incident Investigation Research Association, Yoshida Research Office, Faculty of Sociology, Hitotsubashi University, 1985), no longer introduced.

In addition to the data set, there are also individual documents, diaries, memories, interviews, etc. The number of single materials is huge, most of which are scattered, and some of them are more concentrated and have been widely reported in China (such as "Dong Shiro's Diary" published in Chinese translation earlier than the original text (33), "Diary of Joining the Army in the Japan-China War" that has been excerpted and translated for China. Battlefield Experience of a Supplies Soldier" (34)), and some are foreign translations (such as Rabe's diary "Nanjing's Reality" (35) translated by Hirano Keiko), so here I will only introduce three kinds that are in Japan. Materials that have not attracted enough attention, the rest are cited in the next part:

1. "Journal of the Tenth Army of the Japanese Army"

In "Continuation·Modern History Materials" edited by Takahashi Masayoshi VI "Military Police", Misuzu Study Room, 1982 edition. The content of this edition basically does not involve Nanjing, and the Japanese factions have not paid attention to it. However, as mentioned above, when Japan was defeated, a large number of Japanese military documents were burned, and the log of the Justice Department of the Tenth Army was the "only remaining" (36) log of the Japanese Army's Justice Department. Relevant (the 6th and 114th Divisions are the main force directly attacking Nanjing, the 18th Division and the Guoqi Detachment (37) captured Wuhu and Pukou respectively in order to cut off external reinforcements to Nanjing and retreat the Nanjing defenders) Therefore, the performance of the Tenth Army before and after the capture of Nanjing is not only of great value in understanding the general situation of the Japanese military discipline, but also can be inferred from the performance of the Tenth Army—the Shanghai Dispatch Army—after entering Nanjing. It can be an important reference ( 38).

2. "Central China Front Military Law Conference Log"

Ibid. The Central China Front Army has no Ministry of Affairs, and the Military Law Conference has existed for less than a month. The cases recorded in the diary are mainly the Tenth Army, and there are also a small number of cases of "escape from the army" of the Shanghai dispatched army, which can be used as a supplement to the previous annals.

3. "Diary of an Attorney General"

It was only recently discovered that, as the Minister of Justice of the Tenth Army, the diary of Sekiro Ogawa happened to be a separate copy that could be cross-checked with the diary of the Justice Department of the Tenth Army. In addition to the original meaning of the tenth army's military discipline, Ogawa's diary has two special meanings, namely: first, to prove that Ogawa's testimony for the defense during the Tokyo trial was untrue (to be discussed in detail below); second, to prove that The wartime records of the Japanese military have had gains and losses to the facts (39).

Part Two

It is undeniable that the long-standing controversy over the Nanjing Massacre in Japan is fundamentally related to "positions". However, the lack of sufficient first-hand literature leaves room for "different opinions". So, what do the existing materials in Japan prove? To what extent can it be proved? What questions do you have? Which can not be proved? The following selection should be made briefly.

one

1. Is the attack on Nanjing a predecision or an "accident" of the Shanghai dispatched army?

"August 13" originated from China's "pre-emptive attack", which has now been accepted by many domestic scholars (40). However, although Japan did not take the lead in sending heavy troops to Shanghai, it was not just for passive "protection of Japanese nationals" as the popular Japanese view said. The negative theory stems from Matsui Iwane's defense and Matsui's self-defense during the Tokyo Trial (41). The meaning of this statement in the context of the Nanjing Massacre is that the attack on Nanjing was not a pre-planned plan, but an “accident” of the “forced” development of the war. Therefore, even if there were “a small amount” of atrocities in Nanjing, it was an “accident” caused by the environment.

Needless to say, when the Japanese army dispatched troops, they made grandiose rhetoric about "protecting the lives, property and rights of our residents," and the General Staff Headquarters also had two command line restrictions (42). But this does not mean that the attack on Nanjing was "accidental" or "forced". If we broaden our horizon a little, we can see that after the Showa era, the Japanese army’s “down and overcoming” has become a long-standing trend, and the current Japanese army’s “runaway” is no longer comparable to the so-called “willing to accept the fate of the emperor abroad”. Some people say that Japan’s other It is not an exaggeration to say that the "mechanism of doing whatever you want" (43) has become a reality for the local army. A series of events, from the explosion of Huanggutun and Liutiaogou to the establishment of "Manchukuo", were all initiated by the grassroots, and the central government "had to" ratify them afterward, which is a clear example. The same is true after July 7th. Shibayama Kenshiro, Chief of Military Affairs Section of the Ministry of Army at that time, later recalled that when he and Major General Nakajima Tetsuzo, Director of General Affairs of the General Staff Headquarters, conveyed the central government's "non-expansion" policy to Lieutenant General Kazuki Kiyoshi, commander of the "China Garrison Army", they were not only rejected but also severely reprimanded. is a vivid example (44). In this sense, the presence or absence of orders from the central government cannot be used as an appropriate basis for judging the behavior of the Japanese army.

However, we say that the Japanese army's attack on Nanjing was not an "accident", and there is real evidence, not just a deduction from the general situation. The "War History" materials "Nanjing War History Data Collection" edited and published by the old Japanese military group have the intention of "rectifying" the Japanese army, but as mentioned above, the diaries of the senior Japanese generals collected in this collection are still valuable for understanding the Japanese army's decision-making . We can see from the "Iinuma Shou Diary" that the Shanghai Dispatch Army has not yet set off, and the commander of the army Matsui Iwane has clearly stated: "Partial solutions should be abandoned and the plan should not be expanded." It is more necessary to use the main force in Nanjing than to use the main force in the northern branch." "Nanjing should be captured in a short time" (45), which is completely contrary to what was said in the Tokyo trial. The newly "discovered" part before October of "General Matsui Iwane's Battle Diary" collected in "Nanjing War History Data Collection" II records Matsui's plan and state of mind in more detail. On August 14th, when Matsui learned from the Lu Prime Minister Gen. Sugiyama that he would be in charge of the Shanghai Expeditionary Force, he was "extremely worried" that the military, especially the General Staff, did not use the "Central Branch" as the main battlefield. His "pain" was recorded in his diary the next day: "The Chinese government should be awakened as soon as possible with a hammer." On the 16th, he wanted to persuade the first chief of the general staff, Major General Ishihara Kanji, but instead of talking speculatively, he lobbied the second chief of the general staff, Major General Masaharu Honma, and Sugiyama Rikusang, saying: "The goal should be to attack Nanjing." It is necessary to overthrow the Nanjing government in one fell swoop, so the oppression of the Nanjing government will be more effective in addition to relying on force, economics and finance” (46). The "purpose" mentioned at this time is also the constant goal of the Shanghai Expeditionary Army under the jurisdiction of Matsui and the Tenth Army established later. Therefore, although the central order of the Japanese army to capture Nanjing was issued late, it was a consistent policy for the Shanghai Expeditionary Force.

2. Did the Japanese army ever plan to "peacefully" enter Nanjing?

Japan has a long-standing unidentified statement, that is, when the Japanese army approached the city of Nanjing, it airdropped a notice to persuade China to surrender on December 9, asking the Chinese side to give a reply before noon the next day. Zhongzuo Kuangwu, Shaozuo Ningren of Zhongshan, and Okada waited outside the gate of Zhongshan until 1:00 p.m. and did not receive a reply before launching an attack on Nanjing (47). Today, the letter of persuasion to capitulate is developed into a "peaceful opening of the city" "in accordance with international law" (48). This theory is very popular among the "fictionalists" and "centrists" in Japan. Its subtext, in the words of Watanabe Shōichi: "If China surrenders at this time, nothing will happen." Watanabe also claimed: "Chiang Kai-shek who led the National Government This is the reason why they did not tell the world about the Nanjing Massacre” (49). The "fictitious faction" takes this article persuading surrender very seriously. "The Truth·Nanjing Incident" used the fact that "Rabe's Diary" did not record this event as a basis for the diary's inaccuracy (50). There is no need to argue about not remembering something as a false basis, but whether the Japanese army waited "peacefully" for a day from the 9th to the 10th - from this we can see whether the Chinese army would "not attack" if the Japanese army withdrew. "The sincerity is worth clarifying.

According to the records of Chinese and foreign people in Nanjing at that time, it is not difficult to find out whether the Japanese army stopped attacking from the 9th to the 10th. "Rabe's Diary" began on December 9 with a record that "the air raids continued from early morning." The Japanese bombing did not stop afterwards. Rabe continued on the second day with "the sound of rumbling artillery fire, rifles and machine guns from 8 o'clock yesterday evening to 4 o'clock this morning", and "the city was bombed all day today" (51). The diary of that day also recorded the situation that the Japanese army almost occupied Guanghuamen and advanced to the waterworks by the Yangtze River the night before (the evening of the 9th). Diary of Vautrin on December 9: "Tonight, when we were attending the press conference, a huge shell fell on Xinjiekou, and the sound of the explosion made us all stand up from our seats." Times The daily diary records that "the sound of guns and guns continued at night" (52). Fei Wusheng (George A. Fitch, also transliterated as Fei Qi) wrote Nanjing "diary" on "Christmas Eve, 1937", and the starting time was December 10, of which 10 diaries: "Heavy artillery bombards southern Nanjing The city gate, the bomb exploded in the city." (53) Although this record does not indicate the specific time, it is difficult to judge whether it is before noon of the "advice" deadline, but cross reference with the above quotation can be used as evidence. After Japan's "advice" was issued on December 9, Japan did not stop its offensive, which can also be seen in the records of Chinese people. Jiang Gonggu recorded in "Three Months in Beijing": "(9th) I heard that the enemy had attacked the Qilinmen area and approached the city wall. The sound of guns and artillery was more dense and clear than yesterday. Bafutang in the south of the city has been attacked. The enemy’s artillery shells... After twelve o’clock in the night, the sound of the artillery became louder, and they all fired towards the city; white lights flashed from time to time outside the window.” (54) The “heard” that the enemy arrived at the Qilin Gate can be proved by Japanese military records (55). The attack of the Japanese army on the next morning is recorded in more detail in "Three Moons in Beijing" (56). From the records of these unrelated Chinese and foreign people, we can see that the words and deeds of the Japanese army are completely different: after the so-called "advice" was issued, Nanjing not only failed to escape the attack, but because of the arrival of the Japanese army, it was destroyed by the air-dropped bombs. In addition, the direct bombing of artillery has been added.

The Japanese army is so ignorant, why does the fictional school keep raising it? Perhaps the "fictionalists" thought that the high-level Japanese army intended "peace" and that the bombing was just an order that failed to be issued. So, let us check the Japanese army's own records again to see if there is any "misunderstanding". The Ninth Division of the Japanese Army issued the following order at 4:00 pm on the 9th, after the "Peaceful Kaesong Advice" was issued:

...

2. The division took advantage of the darkness of the night to occupy the city wall

3. Order the troops on the two wings to take advantage of the darkness of the night to occupy the city wall, order the captain of the left wing to put the two teams of light armored vehicles under the command of the captain of the right wing

4. Order the artillery unit to assist the two wing units in combat as needed

5. Order the engineering troops to mainly assist the right-wing troops in fighting

6. Order the rest of the troops to continue to complete the previous tasks (57)

Behind the waiting for the reaction of "opening the city peacefully", it turns out that "use the darkness of this night to occupy the city wall" (58)! Is such an action limited to the Ninth Division, just a "coincidence"? Let us continue to examine the relevant materials of the Japanese army. According to the "Wartime Xunbao" of the Sixth Division:

At midnight on the 9th, the first-line troops decided to go. In order to immediately take advantage of the results of the night attack, the division commander went to Dongshan Bridge at 6 am and ordered the reserve team and artillery team to advance to Tiexin Bridge. (59)

The Sixth Division is also a "night attack". The "combat process" of the 114th Division:

On the night of the 9th, the Qiushan Brigade broke through the enemy's position near Jiangjun Mountain and hurriedly pursued the enemy. On the morning of the 10th, occupied the position near Yuhuatai, reached the front of the enemy, and immediately began to attack. (60)

The Akiyama Brigade is the 127th Infantry Brigade under the 114th Division. The uninterrupted attack from the evening of the 9th to noon of the 10th was recorded in detail in the division's "Battle Detailed Report" and "Wartime Ten-day Report" (61). Not only the documents at the division level, but also relevant records at the grassroots level. If it belongs to the 33rd Infantry Regiment of the 16th Division, record in the "Battle Detailed Report":

On the night of December 9th, the regiment followed the division's "Order of the 33rd Infantry Regiment (missing the First Battalion and the Fifth and Eighth Squadrons) as a right-wing team to attack from the north side of the road (including the road), and the right detachment The five-banners Jiangwang Temple, Xuanwu Lake, 500 meters to the east, and the northeast corner of Nanjing City to form a line (the line includes the right)" commanded, gloriously bathed in the soldiers who accepted the important task of attacking the highlands around Zijin Mountain, and their fighting spirit grew stronger. high spirited. (62)

It can be seen from the above that after the "Peaceful Kaisong Advice" was issued, the Japanese army did not let go of its offensive under the cover of night, and did not keep its promise to wait for the reply from the Chinese side. Total attack" and so on, completely untrue (63).

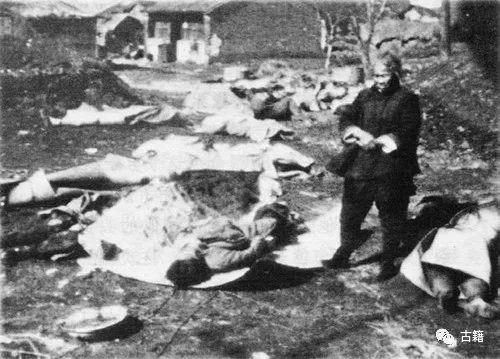

3. Are there a large number of corpses massacred by the Japanese army around Nanjing?

In the past 30 years, especially in the past 10 years, with the reappearance of some important historical materials, it has become increasingly difficult to completely deny the atrocities committed by the Japanese army. The key and symbolic "massacre" is still categorically denied, and it will not give up half a step. The attitude of Oi Mitsu of the fictional school is a typical example of this kind of example of throwing pawns and saving cars. He said in "The Fabricated Nanjing Massacre": "Of course, I am not saying that the Japanese army did not do any wrongdoing at all. There is no such reason why nothing happened to an army of 70,000 people. This is common sense that everyone would think. Staff Officer Onishi slapped the rapist heavily and took him to the gendarmerie, such things undoubtedly happened in various places." (64) And in "Masters! "In the questionnaire survey, he filled in "12" (65) in the answer to the first choice of the number of people killed. "12" means "infinitely close to 0".

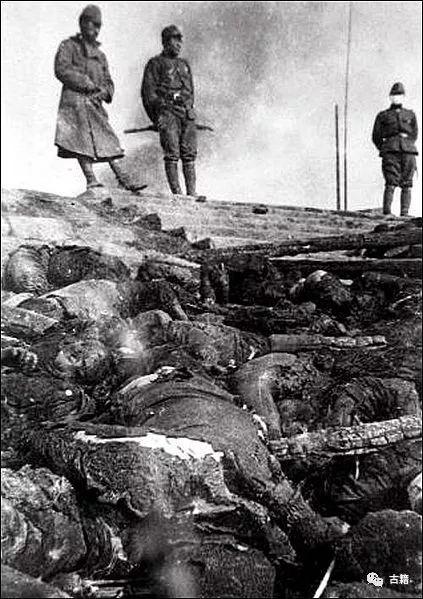

The murdered corpses in Nanjing were finally cleaned up by burying, burning, and dumping in the middle of the river, but they were exposed in broad daylight for a long time. This is the biggest obstacle to denying the Nanjing Massacre, and it is also a key point for the fictionalists to "refute" . Matsui Iwane's full-time adjutant, Major Kadoyoshi Haru, wrote an article "The Battle in the Last Six Months of the China Incident" in his later years. Because the article talked about the large-scale massacre by the Japanese army, it was not published during his lifetime (it was later published in "Coming Together" sponsored by the Old Military Group January 1988 issue). Because of Jiao's special status, once his memories were revealed, controversy immediately arose. The biggest point of contention is "the 120,000 to 30,000 corpses near Xiaguan" (66). According to Kado Yoshiharu, the real culprit who caused these deaths was the Sixth Division, and it was Yong Zhongzuo, Chief of Staff of the Second Section of the Shanghai Dispatch Army Staff Headquarters who gave the order for the massacre, and he was also present when Chang Yong gave the order (67). In this regard, the "fictionalists" and "centrists" unanimously questioned it. "Nanjing War History" thinks that Yoshiharu Kaku's recollection "contradicts a lot and lacks credibility" (68). The "War History Research Notes" attached to "Nanjing War History Data Collection" also believes that "Jiao's misunderstandings, prejudices, and memory mistakes are too numerous to enumerate" (69). However, what Kado Yoshiharu said is not an isolated case.

There is an entry in Matsui Iwane's own diary to prove it. Diary of Matsui on December 20th:

Depart at 10 o'clock to inspect Xiaguan near Yijiangmen. There are still ruins in this area, and the corpses are still abandoned as much as possible. They must be cleaned up in the future. (70)

Masao Yamazaki, the staff officer of the Tenth Army, recorded in his diary on December 17:

Arrived at Zhongshan Wharf on the Yangtze River. …There are countless dead bodies abandoned on the river bank, soaked in the water. There are different degrees of so-called "dead corpses". The Yangtze River is really full of dead corpses. If it is placed on flat ground, it can really become the so-called "corpse mountain". But I don't know how many times I have seen the corpse, so I am no longer a little surprised. (71)

The "Zhongshan Wharf" area is exactly the same place as Kaku Yoshiharu said.

Taishan Hongdao, the chief military doctor of the "China Fleet" command, arrived in Nanjing by seaplane on December 16. At 2:00 pm, he went to the battlefield with the fleet's "Chief of Administration" and "Chief Accountant" to "visit". In your diary for the day:

Starting from Xiaguan Wharf, we drove on a wide road built in a straight line. Rifle bullets were scattered on the road, like sand coated with brass. The grass beside the road was strewn with the corpses of living Chinese soldiers.

Soon, from Xiaguan to Yijiang Gate leading to Nanjing, under the towering stone gate is an arched road, about one-third of the road height is buried with soil. Drilling into the door, it becomes a ramp from Xiaguan. The car moved forward slowly, feeling like it was driving slowly forward on a rubber bag full of air. This car is actually driving on top of countless buried enemy corpses. It is likely that it was opened in a place where the soil layer is thin, and a piece of meat suddenly exuded from the soil during the march. The miserable state is really indescribable. (72)

The area from "Xiaguan Wharf" to "Yijiangmen" here is the same place as Kaku Yoshiharu said. From the same records of these unrelated persons, there should be no more doubts about the veracity of this matter. Moreover, regardless of whether there are civilians among them, since the riverside is not a battlefield, the "dead corpses" are at least the result of massacring prisoners.

In the "Research Notes on War History" attached to "Nanjing War History Data Collection", there is one item specifically "criticized" by Jiao Liangqing. He said: "The description of 'I walked quietly for two kilometers on the river bank road with many corpses lying on it. I am full of emotions. The tears of the army commander flowed down' is really surprising. I love China and love Chinese generals would never drive on abandoned corpses on the battlefield. Moreover, a low-body car would never be able to walk two kilometers on it. I think that only on this point, it is completely fabricated, and anyone can assert .”(73) But such an “assertion” is somewhat arbitrary. This is not only because of the support of what Taishan Hongdao et al. (74) said was "traveling" on "countless corpses", but also because this is an unreasonable thing, and the fabrication will not take such a dangerous path.

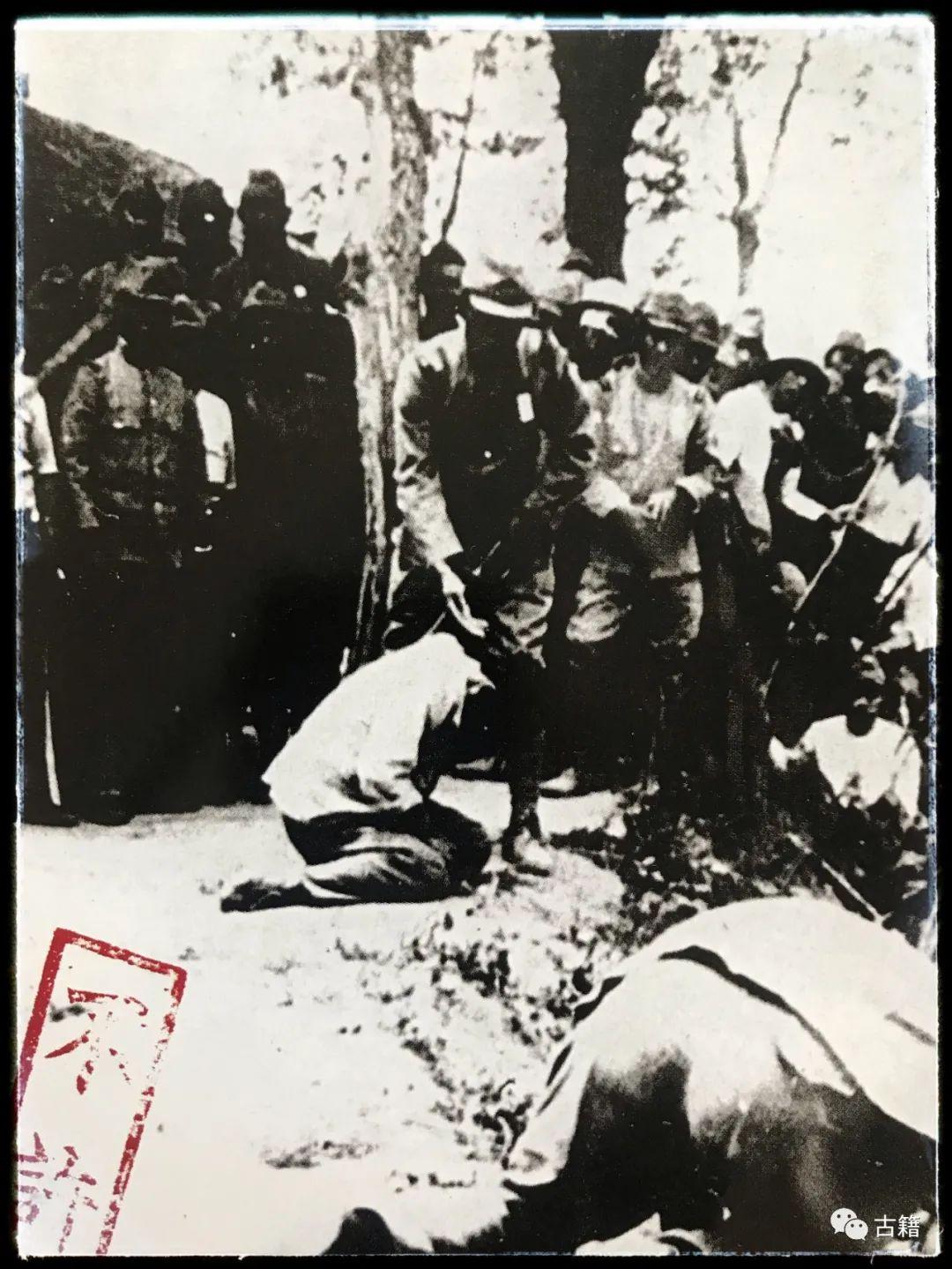

The extent of the massacre at that time was quite reflected in the records of Japanese officers and soldiers. Next, let's take a look at Taishan Hongdao's subsequent records in the diary on the 16th cited above.

About to open the gate and enter the Nanjing side, the piles of enemy corpses were blackened, the iron pockets and gun stabs were also blackened, the metal wire used for the barbed wire overlapped with the burnt wood of the collapsed gate post, and the accumulated soil was also Burnt black, its chaos and sourness are indescribable.

On the hill on the right side of the gate, "China and Japan are incompatible" is engraved, showing the traces of Chiang Kai-shek's anti-Japanese propaganda. When approaching the city, the plainclothes blue cloth padded jackets abandoned by the enemy make the road look like ragged clothes, while wearing khaki military uniforms, The corpses of enemy officers lying on their backs with stiff leather leggings can also be seen everywhere.

The above quotation is just a fragment of what Taishan Hongdao saw on his first day in Nanjing. During his three days in Nanjing, he encountered a large number of corpses wherever he went. For example, on the morning of the next day (17th), in two other places in Xiaguan, I saw "numerous corpses" and saw a Chinese soldier "bloodied" and "begging for mercy" being shot from behind by a "reserve soldier" (75) Shooting at close range; seeing "numerous corpses" along the Zhongshan North Road in the morning; in the afternoon, I inspected Jiang Ting, the commander of the Shanghai Navy Special Marine Corps with Okawachi Chuanchi and others, and saw "numerous scorched enemy corpses"; "Sixty or seventy enemy corpses who 'taste the taste of Japanese knives'" were seen in the river embankment. On the 18th, first in the Lion Forest, I saw "the corpses abandoned by the enemy here and there"; outside the barracks at the foot of the mountain, I saw "scattered corpses"; "(76).

The first-hand materials left at the time of similar incidents are the most convincing proof that there are at least a large number of dead Chinese soldiers around Nanjing—of course not just Chinese soldiers, as we will discuss below. So, are these corpses war dead or massacred soldiers? Before we ascertain this "question" that Japan has been debating, let's first check whether the high-level Japanese army has issued a massacre order.

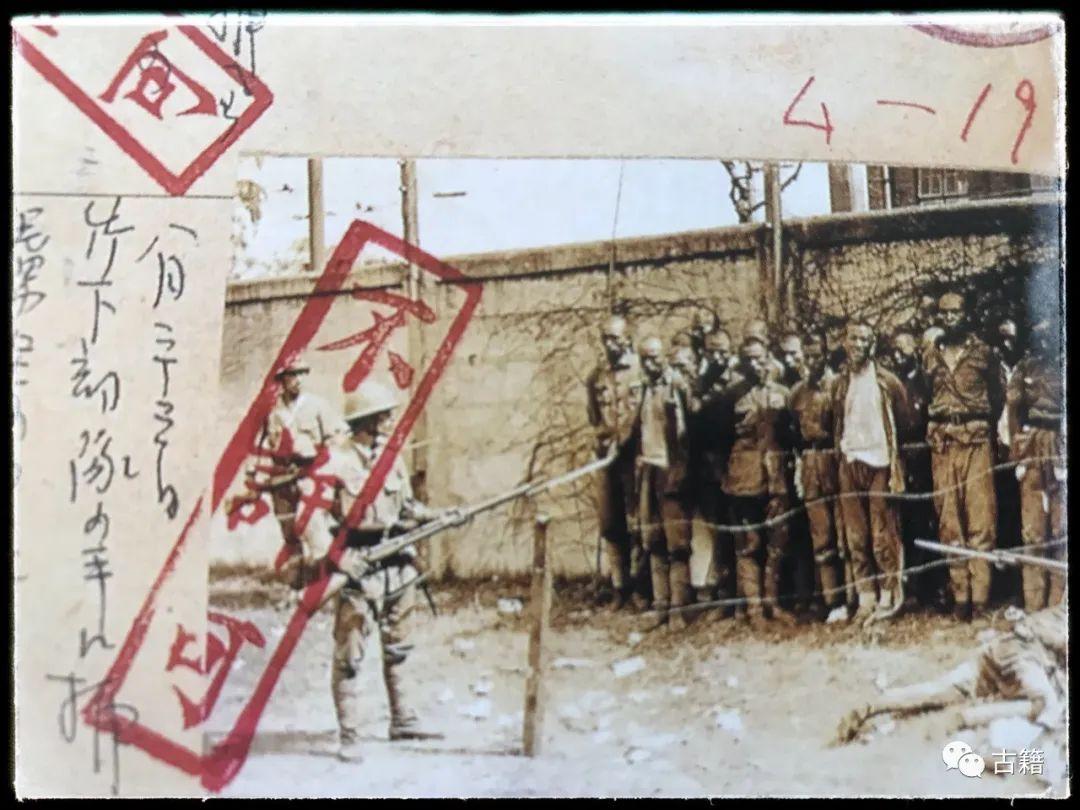

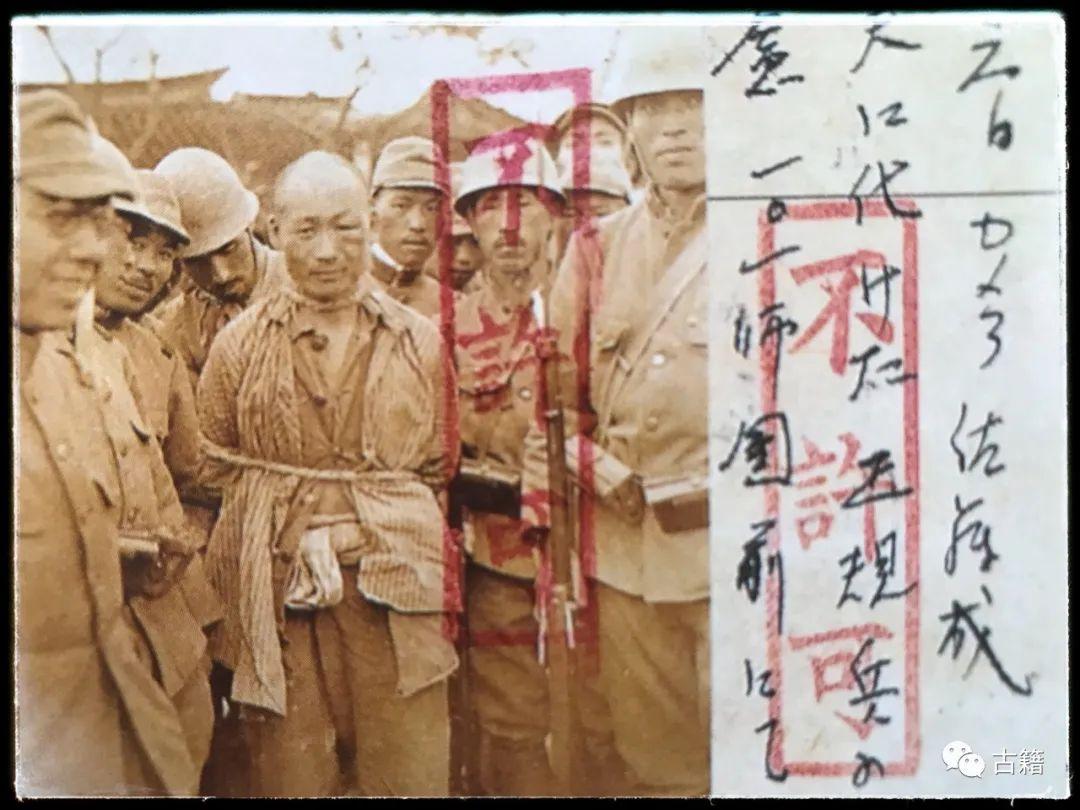

4. During the capture of Nanjing, did the high-level Japanese army issue an order to massacre the prisoners?

During the capture of Nanjing, the Japanese army carried out a large-scale massacre of Chinese captives who stopped resisting. Was this atrocity ordered by the top Japanese army, or was it just the spontaneous behavior of the grassroots troops? Due to the incomplete existing materials, it has brought great confusion to the understanding of this issue. Because the Japanese fictional school does not recognize killing in any sense (77), of course it categorically denies that there was a massacre order. The masterpieces of Japanese military history "War History Series" and "Nanjing War History" also do not admit or tend to deny that the massacre came from their own. Top-down command (78).

Among the existing historical materials, there are three records that clearly refer to the massacre order, namely: Nakajima Imasago, the commander of the 16th Division, wrote in his diary on December 13:

Since the policy of keeping no prisoners is being implemented in principle, it must be dealt with from the very beginning. (79)

The head of the 103rd Infantry Brigade of the 13th Division, Major General Yamada Koji, wrote in his diary on December 15:

He dispatched Honma cavalry second lieutenant to Nanjing to contact him on matters such as the handling of captives.

The order was to kill them all.

Troops have no food, confusing. (80)

The battle report of the 1st Battalion of the 66th Infantry Regiment of the 114th Division:

8. At 2:00 p.m., the following order was received from the regiment leader:

Next record

1. According to the order of the brigade, all the prisoners were killed;

The method is to tie up more than 10 people and shoot them one by one, how about that?

2. Gather weapons and send troops to monitor until new instructions are issued;

...

9. Based on the above order, order the No. 1 and No. 4 Squadrons to sort out and gather weapons, and send troops to monitor.

At 3:30 in the afternoon, the squadron leaders were assembled to exchange opinions on the execution of prisoners. As a result, it was decided that each squadron (1st, 3rd, and 4th squadron) would be divided into equal parts, and they would be taken out of the confinement room in batches of 50. The first squadron was in the south valley of the campsite, and the third squadron was in the depression southwest of the campsite. , the Fourth Squadron carried out an assassination in the valley southeast of the campsite.

However, it should be noted that soldiers must be sent to guard the area around the confinement room, and it must not be sensed when it is brought out.

Each team was ready to end at 5:00 p.m. and began to assassinate, and the assassination ended at 7:30 p.m.

Report to the alliance.

The No. 1 Squadron changed its original plan and wanted to imprison and burn all of a sudden, but failed.

The captives had seen through it and were fearless. They stretched out their heads in front of sabers and stood up in front of spears. (81)

Because these three pieces of material came from the time of the incident, they belonged to "first-hand" and have special value in restoring whether the massacre of prisoners came from orders, so the Japanese fictionalists and some centrists spared no effort to add "argumentation" in detail, known as Nakajima and Yamada's The records have nothing to do with the massacre order, and the detailed massacre records reported by the 1st Battalion of the 66th Regiment contradict the facts in terms of time and content, so they are fabricated.

I have extensively collected relevant documents at the time of the incident and referred to the recollections of the parties afterwards to prove that the above records are clear evidence of the massacre order (82). The main arguments are as follows: 1. The order issued before dawn by the 30th Brigade under the jurisdiction of the 16th Division that "all teams are not allowed to accept prisoners until the [new] instructions of the division" (83) and the spirit of Nakajima's diary The reason why it is certain that this order refers to the massacre of prisoners is because Major Yoshio Kodama, the adjutant of the 38th Regiment under the 30th Brigade, recalled the following about this order:

One or two kilometers closer to Nanjing, in the mixed battle, the adjutant of the division sent the division's order over the phone, "Do not accept the surrender of the Chinese soldiers and deal with them." Such an order is surprising. Shocked. Lieutenant General Nakajima Kinzago, the head of the division, is a charismatic and cheerful general, but this order cannot be accepted anyway. For the army, it was really surprising and confusing, but as an order, it had to be conveyed to the brigades, and the brigades did not report this matter afterwards. (84)

Kodama’s recollection stemmed from the fact that before Nakajima’s diary caused controversy, it was impossible to have a targeted awareness of the problem, so the “no” he said should be the most direct and clear proof of the “no” of the Thirty Brigade. From the diary of Nakajima Kinzago to the order of the 30th Brigade to the memories of Yoshio Kodama, divisions, brigades, and regiments are "completely completed" and passed down in one line. room for. Second, not only is the "context" of Yamada's diary devoid of

Articles are uploaded by users and are for non-commercial browsing only. Posted by: Lomu, please indicate the source: https://www.daogebangong.com/en/articles/detail/Cheng%20Zhaoqi%20An%20Introduction%20to%20the%20Existing%20Historical%20Materials%20of%20the%20Nanjing%20Massacre%20in%20Japan.html

支付宝扫一扫

支付宝扫一扫

评论列表(196条)

测试